The Changing Geography of the Opioid Crisis

America’s opioid crisis has reached epidemic proportions. Opioids have killed more than 350,000 people since 1999 and nearly 50,000 in 2017 alone.

In contrast to previous deadly drug epidemics like the heroin crisis of the 1970s, which was highly concentrated in cities and urban areas, opioids have affected rural areas the most: Over the past two decades, deaths from opioid overdoses have climbed by more than 700 percent in smaller rural areas, versus less than 400 percent in cities and metropolitan areas. But this geography appears to be reversing as deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl have climbed rapidly in cities and metros. Such deaths are expected to soon eclipse deaths from opioid overdose in rural, non-metro areas.

A recent study by a team of researchers at Syracuse University, the University of Iowa, and Iowa State University takes a deep dive into the changing geography of the opioid crisis. Published in the journal Rural Sociology, it tracks opioid deaths in the more than 3,000 counties that make up the 48 contiguous U.S. states. And, using data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), it breaks out these deaths from distinct types of opioids: heroin and opium, prescription opioids like methadone, synthetic opioids or unknown narcotics, and so-called multiple-cause deaths from two or more opioids.

The study finds that the opioid crisis takes different forms in urban and rural America. While the urban opioid crisis is a crisis of heroin and illegal drugs, the rural opioid crisis of prescription drugs is largely a story of growing spatial inequality and of places left behind, most often occurring, as the authors note, in places that tend to have a declining industrial base.

Opioid overdose mortality rates per 100,000 (age-adjusted) in 1999-2001 and 2014-2016

The second wave involved heroin. This crisis is more urban, with metros having consistently higher death rates than rural or non-metropolitan areas.

The third wave of the opioid crisis is synthetic opioids. This, too, is more of an urban crisis, with death rates being highest in large metro areas and micropolitan areas, and lowest in rural areas.

There is a final and more troubling strand of the opioid epidemic: Places where opioid deaths come from a mixture of prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids—what the study refers to as a “syndemic” crisis. Four percent (129 of 3,079 counties) fall into this category. This syndemic opioid epidemic is concentrated in the eastern third of the nation: in Maryland, Massachusetts, rural Appalachia, stretching into Indiana, and in Michigan. A third cluster is located around Santa Fe, New Mexico. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent, or 82 counties) of syndemic counties are in metropolitan areas, with 36 percent (47 counties) in rural or non-metro areas.

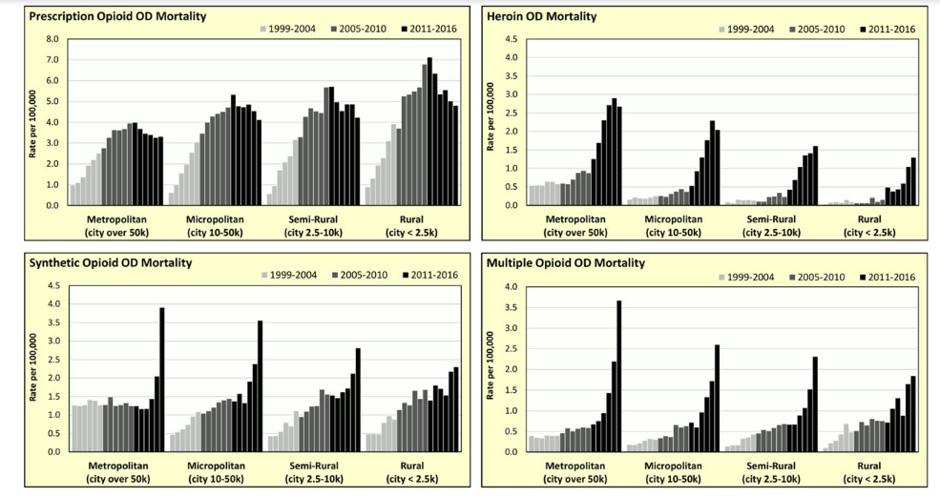

Overdose mortality by opioid type per 100,000 between 1999 and 2016

A common theory for the opioid crisis is that it developed from abuse and over-prescription of legal opioids. The study, however, finds this theory holds only in rural areas. It reads: “Rural industrial decline left a legacy of unemployed and underemployed people with some form of work disability,” and notes that “… a plausible treatment for work-related pain, likely involving opioids prescribed by a health provider, helped start the cycle of opioid addiction that would culminate in the current crisis.”

But another part of the explanation comes from the fact that many of these places have long histories of drug and alcohol abuse. As the study points out, “the current rural opioid crisis is part of a broader drug problem, taking root in smaller communities with an existing drug user population and/or socioeconomic conditions favorable to drug abuse.”

The researchers find only limited support for the “deaths of despair” theory, which contends that the spike in opioid deaths is a function of the deepening despair brought on by economic decline and the unraveling of the traditional support structures of family and community. This theory holds only for rural counties that were bound up in the early prescription opioid epidemic, and not in urban areas, which have been much more affected by heroin and illegal opioids.

Across the board, both rural and urban communities that are centers of the opioid crisis are declining industrial communities with older, whiter, and less educated populations. These are the places that have been hardest hit by globalization, deindustrialization, and the shift to a highly urbanized knowledge economy—places which, as the study puts it, “are remnants of the 20th century industrial economy that are becoming increasingly dissimilar from the rest of the nation demographically, economically, and culturally.”

This article appeared in City Lab. Read more here.